Artworks by Mofokeng, Santu

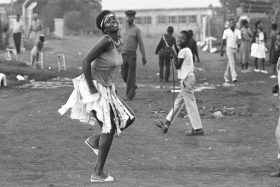

![Sm 1018 04]()

"Comrade Sister," White City Jabavu

![Sm 1018 01]()

23rd Player, White City Jabavu

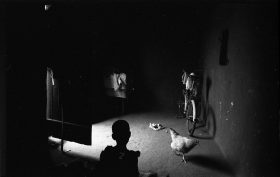

![Sm 1041 02]()

Afoor Family Bedroom, Vaalrand

![Sm 1034 04]()

Aus/Luderitz, Namibia

![Sm 1018 02]()

Avalon Cemetery, Chaiwelo

![Sm 1004 11]()

Buddhist Retreat, near Pietermaritzburg

![Sm 1018 03]()

Chicken Farm Shebeen, Rockville

![Sm 1034 08]()

Chief More's Funeral, GaMogopa

![Sm 1004 07]()

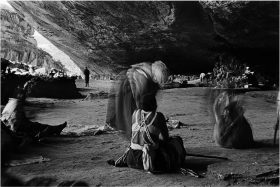

Christmas Church Service, Mautse Cave

![Sm 1004 14]()

Christmas Church Service, Mautse Cave

![Sm 1004 04]()

Church of God, Motouleng

![Sm 1034 05]()

Concentration Camp Graves, Brandfort

![Sm 1028 02]()

Democracy is Forever, Pimville

![Sm 1045 02]()

Doornfontein, Downtown JHB

![Sm 1031 01]()

Dust-storms at Noon on The R34 Between Welkom and Hennenman, Free State

![Sm 1004 03]()

Easter Sunday Church Service

![Sm 1004 13]()

Eyes-wide-shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens

![Sm 1034 07]()

Farm in Modderpoort

![Sm 1034 01]()

Farm Murder Landscape

![Sm 1034 06]()

Fevriary 3 Mass-grave, Mozambique

![Sm 1018 05]()

Fire-wood Seller, Orlando East

![Sm 1018 07]()

Golf in Zone 6, Diepkloof

![Sm 1018 06]()

House #40, Kliptown

![Sm 1004 05]()

Inside Motouleng Cave, Clarens

![Sm 1034 03]()

Katse Dam, Lesotho

![Sm 1014 02]()

Laying of Hands, Johannesburg – Soweto Line

![Sm 1004 09]()

Mautse Landscape, Ficksburg

![Sm 1041 01]()

Moth'osele Maine, Bloemhof, May 27, 1994

![Sm 1004 08]()

Motouleng Landscape with Poplar Trees and Altar

![Sm 1018 09]()

Mrs. Nhlapo, Rockville

![Sm 1004 06]()

Offertory/Shrine, Motouleng Cave, Clarens

![Sm 1014 03]()

Opening Song, Hand Clapping and Bells

![Sm 1034 09]()

Out-House of a Soft-Drink and Beer Store, Namibia

![Sm 1004 02]()

Prayer Service at the Altar on the Easter Weekend at Motouleng Cave – Free State

![Sm 1028 03]()

Robben Island as You Have Never Seen it Before

![Sm 1004 12]()

Sacral Animals, Motouleng Cave, Clarens

![Sm 1004 01]()

Sangoma Sisters Gladys and Cynthia Leading Initiates in the Afternoon 'Ingoma,' Clarens

![Sm 1018 08]()

Senaoane, Soweto

![Sm 1018 10]()

Shebeen, White City

![Sm 1045 01]()

Shembe Church, Inhlangkazi Mountain, KZN

![Sm 1050]()

Sisters Dorah and Athalia Sitting in the Front Room, Tzaneen

![Sm 1034 11]()

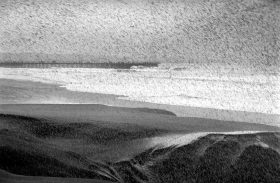

Skeleton Coast, Namibia

![Sm 1031 02]()

South Beach, Replacing of Sand Washed Away During The Floods and Wave Action, Durban

![Sm-876]()

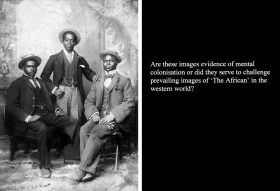

The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950

![Sm 1014 01]()

The Book, Johannesburg – Soweto Line

![Sm 1014 04]()

The Drumming, Johannesburg – Soweto Line

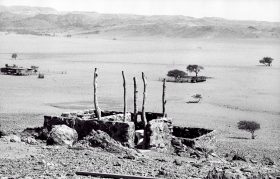

![Sm 1034 10]()

The Namib, Namibia

![Sm 1004 10]()

U-Drive Rent-A-Car, Little Switzerland

![Sm 1031 03]()

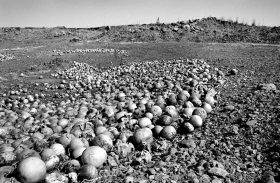

Undersized, Stunted-in-growth and Rotting Melons Dumped in The Veld Outside Kroonstad, Free State

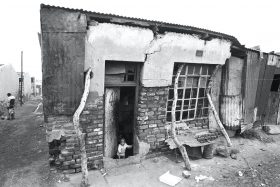

![Sm 1041 03]()

Vaalrand Shack, Bloemhof

![Sm 1034 02]()

Vlakplaas, Pretoria

![Sm 1028 01]()

Winter in Tembisa