On Motherhood and Other Myths

On the second Sunday in May, many countries celebrate Mother's Day. However, it is not only on this holiday that the ambivalent subject of motherhood is omnipresent. The concept and its meaning are continuously negotiated in private and public, and on personal and political levels every day. While the origins of each country's Mother's Day differs—for example, the Association of German Flower Shops introduced Mother's Day in Germany in 1923—today we remember Anna Jarvis, the American women's rights activist, whose efforts originally led to the initiation of Mother's Day in the United States in 1914.

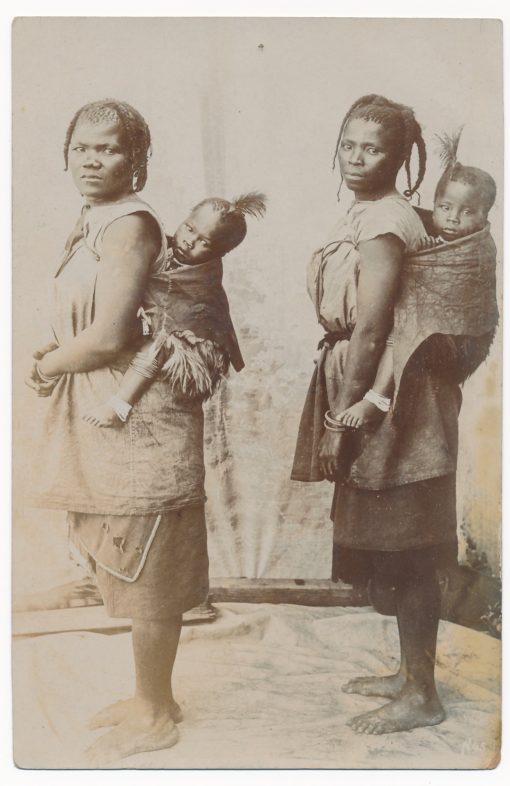

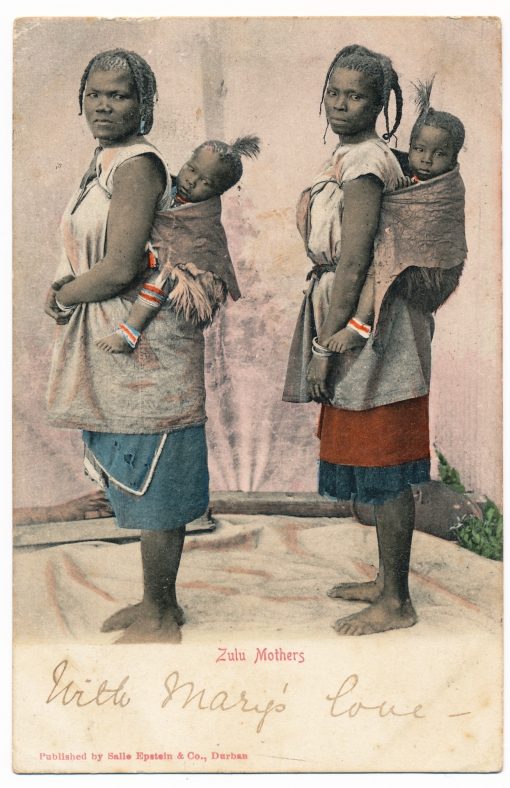

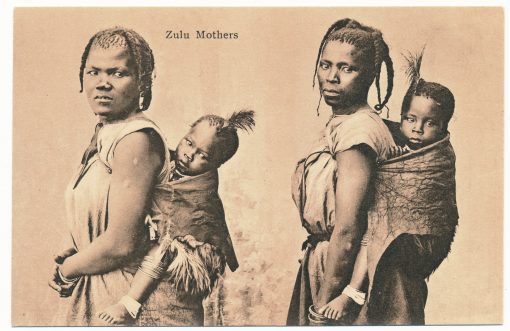

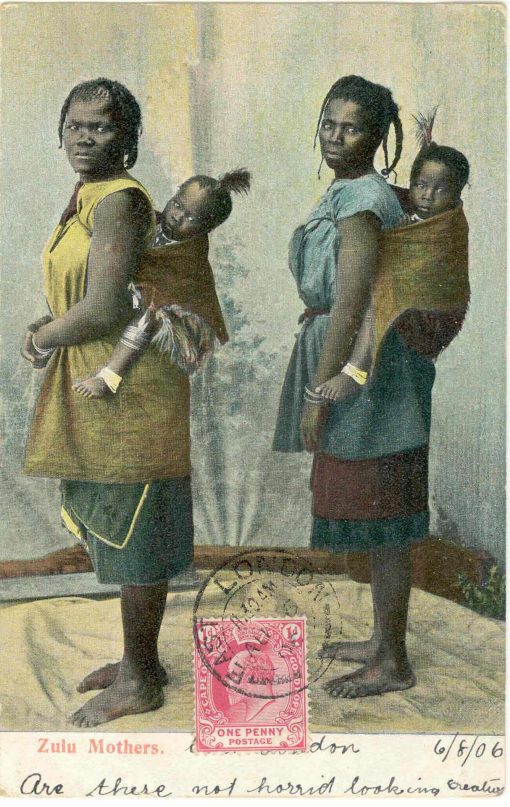

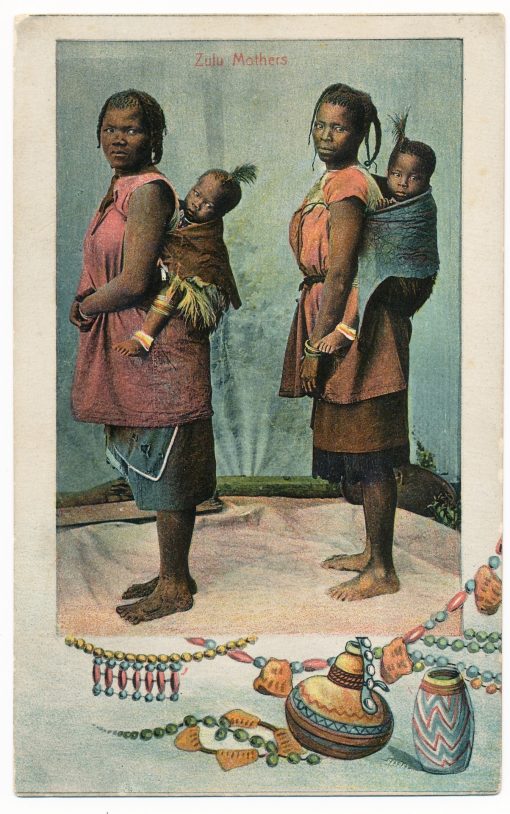

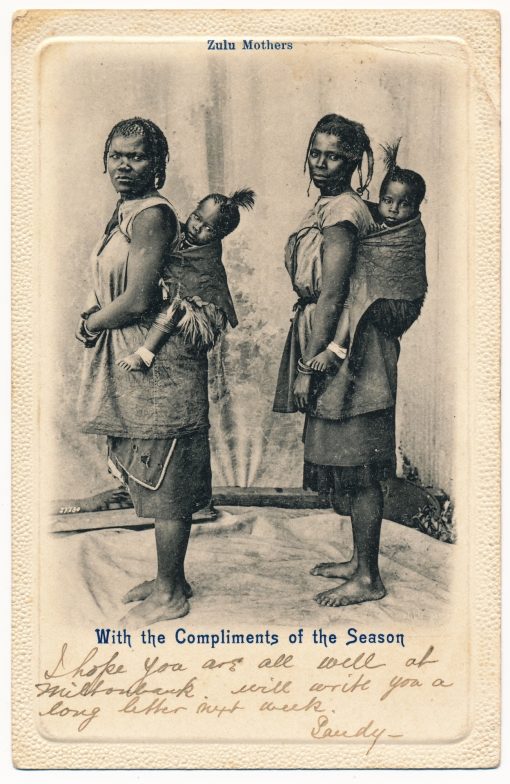

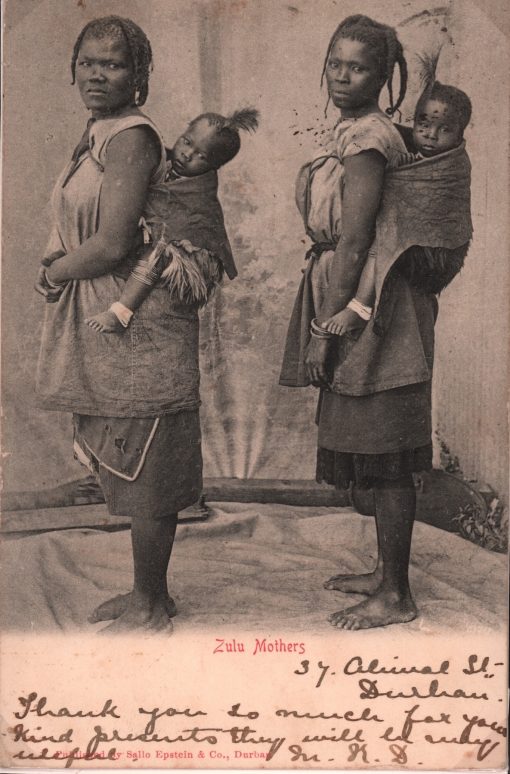

In 2013, The Walther Collection presented Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive, an exhibition that critically examined stereotypical representations of Africans – including the widely reproduced picture "Zulu Mothers," which circulated in large numbers in Europe as a photograph, postcard, and carte de visite. The caption of such a postcard marks the women photographed in two ways: as mothers and especially as the other mother, namely the African mother, thus creating a clear distinction from the Western concept of motherhood.

The gelatin or collodion printing technique used suggests that the photograph "Zulu Mothers" was taken in the late 19th century. Postcards with African motifs formed only a small part of the global postcard archive. Yet they were of importance: The golden age of postcard production and distribution coincided with the period in which the European colonial powers massively expanded their administrative structures throughout Africa. Thus, African postcards of this kind reflect the complex relationships between the photographer and the subject photographed, as well as between motif and viewer. They tell of the colonial conquest and economic exploitation of Africa. While some of the photographs show pictures of landscapes, urban architecture and industrial progress, one focus of African postcard production was on depicting ethnicity and racialization, which visualized and staged Africans as the Other, the Foreign, and the Exotic. The photo print at hand is also of this kind.

Christraud M. Geary identified the women as members of the Bhaca, a Zulu-speaking group from the south of the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal, on the basis of given clothing and hairstyles. The arranged pose, which shows the two women in full body profile, allows an optimal view of the leather slings with which the two mothers have tied their children to their backs. It is considered to be the most widely used motif in South Africa and was particularly popular with European customers. Geary explains the development of this very image into an icon – by way of the photograph – combines motifs of the own and the Other, that is, the concept of motherhood that is widespread in the West with the image of the Western stereotype of the African mother carrying her child directly on her body. Not least through its inscription, the women are – to use the famous words of the radical psychiatrist and critic of colonialism Frantz Fanon – "captured, fixed and emptied" as Zulu and mothers: as archetypal representatives of an African tribe and as timeless and static images of the Zulu mother, thus inscribing themselves in the collective memory of the mostly Western viewers. This and similar picture postcards of the late 19th and early 20th centuries not only created images of oppressed and stereotyped African women, but contributed to the spread and consolidation of racist and sexist world views more generally, and were therefore strongly criticized within postcolonial and feminist discourses.

Processes of stereotyping women and their role in society span space and time to the present day. The theme of motherhood is still characterized by one-sided and mystic notions that seem largely unchanged from centuries-old traditional roles and their interdependence with other social categories such as gender, class, and race. As a current example, Sheila Heti's widely celebrated autofictional novel Motherhood, first published in 2018, has been translated into over 15 languages and was published in German in February 2019. Its nameless, white, almost 40-year-old first-person narrator not only struggles with the very personal question of whether to mother or not to mother, but also with the widespread myth that defines motherhood as the narrative to which the woman is bound. The protagonist describes: "I know a woman who refuses to mother, refuses to do the most important thing, and therefore becomes the least important woman. Yet mothers aren`t important, either. None of us are important." This incendiary passage refers to the controversial discussion about the value of women and mothers in today's society, and thus problematizes a kind of work that is mostly performed by women and mothers: the invisible and unpaid so-called care-work, also known as emotional labor, which is mostly located in the area of the private, the family. The theologian and ethicist Ina Praetorius therefore calls for greater visibility and appreciation of care-work within society. The co-founder of the association Wirtschaft ist Care (Economy is Care) sees the origin of the disdain for care-work in the etymological roots of the term "family," which comes from the Latin famulus and means "servant." For a long period of time, women and children were legally regarded as the property of men, and the work that was done at home was therefore not part of formal work.

In many countries, approaches to implementing gender equality are prescribed by law. However, the recent study Women, Business and the Law 2019: A Decade of Reform by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) stresses that the legal situation in only six countries worldwide guarantees women absolute equality by law – these are Sweden, Belgium, Denmark, France, Latvia and Luxembourg. But even legally anchored – and thus theoretical – equal opportunities are not sufficient for the practical implementation of de facto gender equality. With regards to Germany, the study particularly criticizes the widely diverging gender pay gap and gender care gap. According to the current Second Equality Report of the Federal Government of 2018, women in Germany perform on average 52.4 percent or 1 hour and 27 minutes more unpaid care-work per day than men. The gender care gap among mothers, who belong to the category of heterosexual couples with children, is as high as 83.8 percent – a difference that can no longer be ignored, especially on a political level. The Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ) confirms that the goal of gender equality in everyday life has not yet been achieved. Consequently, the main objectives of gender equality policy are, on the one hand, economic enhancement of care-work and, on the other hand, a reform of the underlying conditions which currently make it difficult to reconcile gainful employment and informal care-work – not only for mothers but also for fathers.

In view of such facts, flowers for Mother's Day may conjure up nothing more than a diverting smile on the faces of our mothers. But it is crucial to remember that motherhood is not a universal category: neither the woman and mother exist as such. Motherhood is lived and celebrated differently depending on time and culture. Cheers to the visualization and appreciation of different stories of motherhood!

– Livia Wermuth